This past weekend I finished reading Richard Dawkins' new book, The God Delusion. Dawkins, for those who haven't heard of him before, is a well-known British biologist most famous as an outspoken advocate of evolution. (Yeah, he's the scientist spoofed on South Park having a relationship with Mrs. Garrison.) The God Delusion, which came out late last year, has been a fixture on the bestseller list and has raised a lot of controversy for its polemical criticism of religion.

I share his viewpoint that believing in the supernatural is irrational, and that religion is too often granted immunity from criticism. Dawkins' book is full of great quotes from people ranging from Douglas Adams to Thomas Jefferson that humorously buttress his points. Who knew, for example, how much that champion of modern conservatism, Barry Goldwater, detested the influence of the religious right?

The actual substance of the book, however, is uneven. As much as Dawkins is a witty and engaging writer--regardless of your views, the book is readable throughout--I doubt he accomplishes the stated goal of his book: to convert believers into atheists.

I've said before that telling people they are idiots and simpletons, or worse, is not generally the best way to persuade them of your cause. Dawkins' methods, which include using statistical improbability to show the improbability of God's existence, are not going to have the slightest effect on someone who does believe in God.

Dawkins attacks religion for engendering fundamentalism, bigotry, hostility to science, and other negative influences. Of course, it's easy to knock down such targets as the Taliban, homophobia, literal interpretation of the Bible, etc., but everyone is aware of these externalities and yet most people continue to believe in God!

A chapter on how meme theory might explain why religion is so widespread throughout human cultures was the least interesting. I guess it sounded too hypothetical. More appealing to me was Dawkins' later argument that humans can act morally without religion, which I agree with. His explanation for this is that we have nurtured altruistic genes (which better our odds of survival) through natural selection. Yet of course, while atheists are definitely capable of being good, that does not mean an absence of religion is the end of all conflict. (The aforementioned South Park episode featuring rival groups of atheists battling each others brilliantly showed how human nature inevitably leads to conflicts.)

Another point I agree with Dawkins on, though much less polemically so, is on the religious indoctrination of children. Dawkins repeats ad nauseum how a child should not be referred to as a "Muslim child" or "Christian child" because at that young an age he does not have the capability to decide for himself the matter. (No one would call a child a "Republican boy" or "Democratic girl".) I don't have a problem with children being brought up in the religious tradition of their family, but surely at some age it only makes sense that a child be free to decide for himself whether he wants to be part of that religion, another religion, or no religion at all.

Dawkins is at his best at the end of the book when he evokes the wonders of science to show how scientific inquiry reveals the universe to be even more awe-inspring and amazing than people (especially religious fundamentalists) give it credit for. I wish he had chosen to emphasize this approach more, because I think it would be the one that's most convincing.

A book like Carl Sagan's The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark, which explains the scientific method and promotes rational thinking, or even the one I'm reading now, A Short History of Nearly Everything, does more to enhance science's stature and increase the general public's scientific interest. That is the best way for Dawkins to achieve his goal of a less fundamentalist, less anti-science world. Unfortunately the tone of his own book does not help.

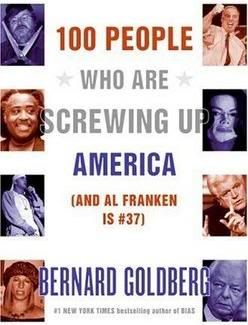

Despite his unflattering performance, I nonetheless ventured to read Goldberg's book for myself. Now it would be easy to poke fun of the man for being a "square" and hopelessly "out-of-touch" when he rants about the increased proliferation of sex, profanity, and other crass elements into the popular culture. However, between his predictable take on stale subjects such as obscene rap lyrics and frivolous lawsuits, Goldberg does raise some valid points. One segment that especially resonated with me was his complaint of the cheapening of "serious news" into "murder-of-the-week crime shows or vehicles for dumb celebrity ass-kissing interviews." Having worked so long for CBS News and

Despite his unflattering performance, I nonetheless ventured to read Goldberg's book for myself. Now it would be easy to poke fun of the man for being a "square" and hopelessly "out-of-touch" when he rants about the increased proliferation of sex, profanity, and other crass elements into the popular culture. However, between his predictable take on stale subjects such as obscene rap lyrics and frivolous lawsuits, Goldberg does raise some valid points. One segment that especially resonated with me was his complaint of the cheapening of "serious news" into "murder-of-the-week crime shows or vehicles for dumb celebrity ass-kissing interviews." Having worked so long for CBS News and

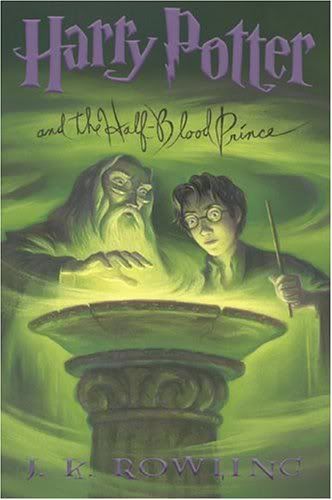

It was terrific. The preceding book,

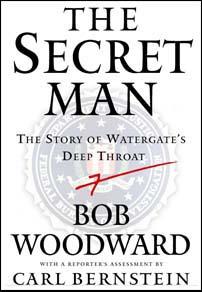

It was terrific. The preceding book,  For 33 years, the identity of "Deep Throat"--the anonymous source who helped

For 33 years, the identity of "Deep Throat"--the anonymous source who helped  Anyhow, I don't find fault with Woodward for skimming over the Watergate story; after two bestselling books (

Anyhow, I don't find fault with Woodward for skimming over the Watergate story; after two bestselling books (